A Gallipoli Landing / Centenarian

George (Sonny) Skerrett

George (Sonny) Skerrett, one of eight children of George Henry Skerrett and Hannah Skerrett, née West, was born on 17 September 1893 in Bluff. As a young man, George started an apprenticeship as a dispensing chemist. According to one of his daughters, Eva Boyer, he didn’t like the job and chose to work on the wharf in Bluff instead. When World War One broke out in 1914, George was already in the territorials. On 15 August 1914 he joined the Otago Infantry Battalion and on 14 October that year, set sail for Egypt – via Hobart – aboard the Ruapehu. During the trip to Egypt the ship’s first aid dispenser died and was buried at sea. Because of his training as a chemist, George took on the role and ended up in the Medical Corps.

When the Otago Regiment – led by the Southland Company – landed ashore at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, George experienced the full horror of war.

George shared his experience of that time with his granddaughter, Jill Skerrett, ahead of his 100th birthday.

We didn’t land until three in the afternoon. Ashore, it was frightful. Terrible. I particularly remember the Armistice Day on May 24th 1915. There had been waves of Turkish attacks, and they were all shot down.

The Turks applied for the armistice to bury the dead. I went out with four doctors, couldn’t do much for those that were alive, just bandaged them. There were 4,000 Turks buried that day. I never saw anything like it in all my life. I cried all day, all afternoon, I couldn’t stop. Six of my mates, one a cousin... we did everything together swum and played tennis... they were all out there dead. I looked for them but never found them. Some of the bodies had been lying out there for over a month and they just fell to pieces in the 100 degree heat. I shouldn’t have gone out as I think it was the start of my troubles with fever.

George (third from left) in Wellington

“They spread lime over the bodies, but that didn’t do much good. It didn’t do me much good either... From my treatment station, that had one doctor and four orderlies, it was a mile to the beach. All we could do was bandage the wounded as best we could, slip a morphia tablet under their tongues and then walk with them down to the beach. Simpson and his donkey took the ones who couldn’t walk. We were shelled continuously, shrapnel shells falling on both sides. Why I never got hit I’ll never know. I still remember the beach. There were a couple of thousand men lying there in all shapes and sizes and forms, all wounded and sick. Some of them thought they weren’t as bad as others. We could only treat a certain number of them. The badly wounded, they’d say, ‘you go and find someone else to look after’, and they just lay there and died. Some chaps found an Australian and New Zealander dead in each other’s arms. I still think about Gallipoli quite a bit. It accomplished nothing".

At the end of August 1915, George was evacuated to a Cairo hospital suffering from fever. It was the last thing he remembered for three weeks. From there, he was taken to a fever hospital for three months, and later returned to New Zealand onboard a hospital ship on 1 January 1916.

Eva remembers that throughout his life, George was haunted by the memory of his friends whose bodies would never come back home. Though he barely mentioned it to his family, it troubled him because tīkanga demands they should have been brought back to New Zealand.

On his return to New Zealand, George went home to Bluff. He married Lylla Wood and they had nine children together. His youngest daughter, Eva Boyer, described George as a good humoured man and she was never aware of any violence. Eva said her father made sure the family never missed Sunday school or church.

‘He was a very good father and we had very good times. He was a shocking driver. Had his licence until he was 92 or 93. The grandkids loved going over there. He loved going to Bluff, and Colac Bay, Riverton where he first farmed.’

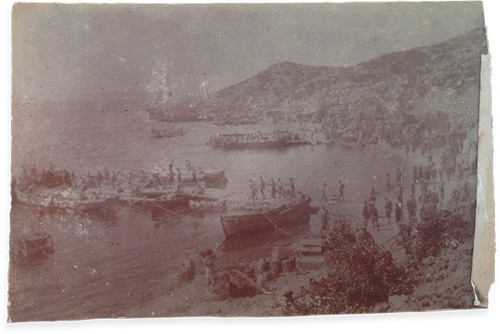

Anzac Beach (two days after landing, 27 April 1915.

He worked the farm on his return. A lot of Māori couldn’t access the farm loan scheme. He got some help from my mother’s side, from Granny,’ said Eva.

George’s periods of service included 161 days in New Zealand and one year, 101 days overseas in Egypt and Gallipoli – a total of one year and 262 days. He was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal, Victory Medal Gallipoli Lapel Badge and Gallipoli Medallion.

George aged 90 years’ old.

George was last interviewed by family in his 100th and final year. At his birthday celebrations he knew everyone by name, including his 33 grandchildren. Diane believed her grandfather was the last surviving Māori veteran of World War One.

George passed away on 30 June 1993, in Christchurch.

For immediate whānau members wishing to have their own copy of the full video, please contact Whakapapa Ngāi Tahu on 0800 KAI TAHU (0800 524 8248).